Navigating murky waters: the impact of AI technologies, precarity, and inequality on the lived experiences of underrepresented cultural entrepreneurs

by Paromita Saha

The creative sector is where cultural entrepreneurs from marginalized groups are seen to possess freedom and autonomy to express their cultural identity and achieve equal participation (McRobbie 2018: 24). Yet, extant scholarship documents how they face persistent patterns of inequality, and discrimination because of the structural biases that exist within the CCI (Sobande, Hesmondhalgh & Saha 2023, Brook, O’Brien & Taylor 2020).

The emergence of disruptive technologies supposedly offers the potential for creatives from underrepresented communities to imagine as well as articulate emancipatory futures and narratives. Historically, marginalized groups face barriers of entry accessing disruptive technologies.

There’s the question of how machine learning systems (LLMs) and generative AI impacts productivity and sustainability, as well as the lives of those who work within the creative ecosystem (Black et al 2024). The livelihood of a creative is a delicate balancing act of developing one’s craft while navigating the precarity due to the “fragmented and individualized nature of the work” (Comunian & England 2020: 115).

This article asks if the incorporation of AI technologies in the work practices of cultural entrepreneurs from underrepresented communities contributes to creative impact, sustainability, and equal participation (McRobbie 2018). I spoke with seven cultural entrepreneurs from the UK and Europe to find how working with AI tools intersects with their lived experiences of precarity and inequality within the CCI.

The paradox of using AI

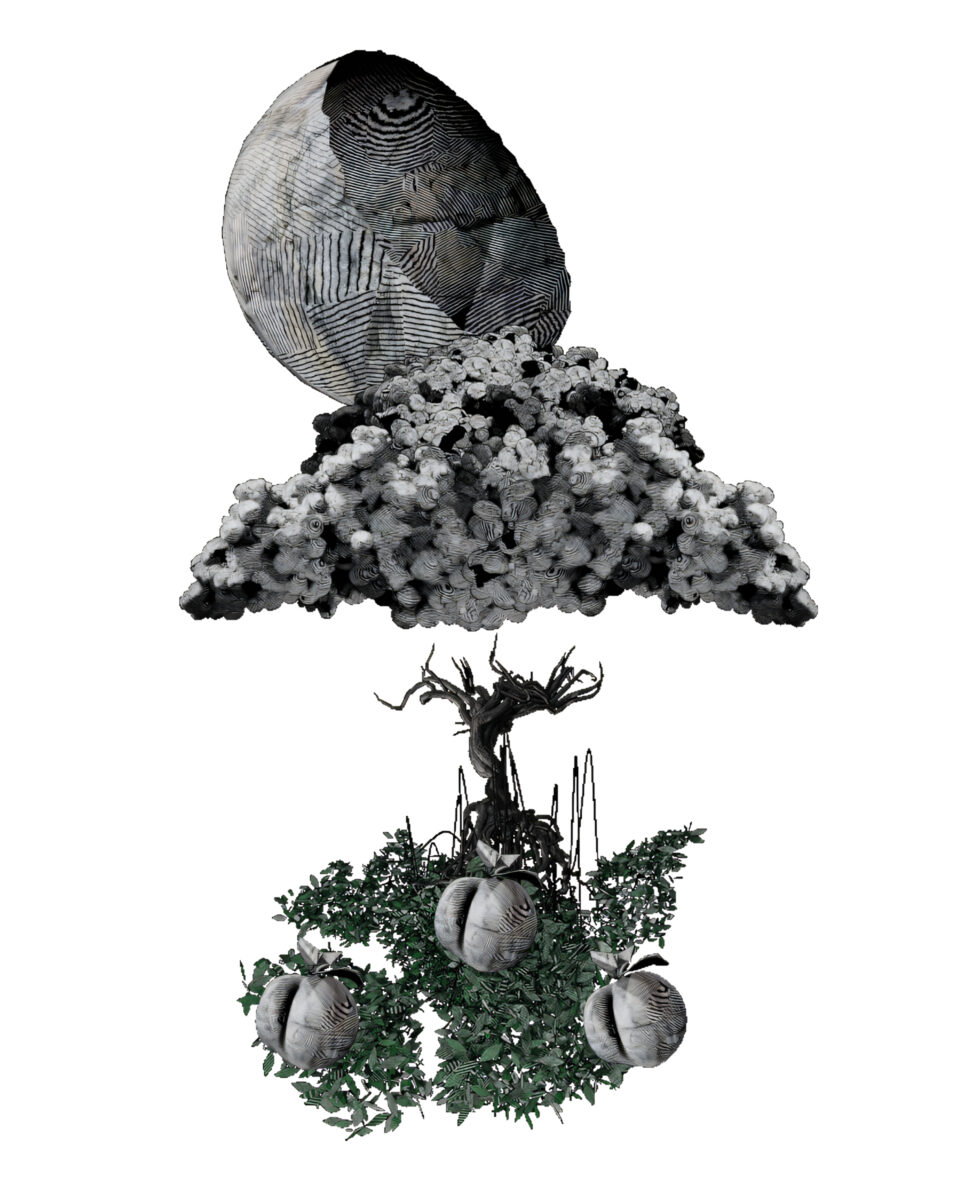

The revolutionary capacities of disruptive technologies such as AI open limitless opportunities for creativity and innovation (Siemon et al 2022). Participants find themselves in a paradox whereby they see the benefits of AI technologies on their creative practices. For example, tools such as Stable Diffusion and Midjourney can bring to life their stories in the form of creating immersive and multisensory art. London based Saudi artist Daniah Alsaleh says “the integration of technology (coding and machine learning) into my practice has expanded my creative possibilities”. It allows her to explore themes such as perception and memory in relation to her Middle Eastern identity as well as to engage with audiences on multiple levels.

Yet, there is a frustration of how generative AI technologies such as Midjourney reinforce existing biases in the form of negative and harmful stereotypes. This is the result of large, biased data sets used to train AI programs. Participants cite problematic representations including the sexualization of girls, hyper feminine trans-individuals or colonist depictions of South Asian identities. Considerable effort is spent on the arduous and mundane process of iterating prompts, as Berlin based filmmaker and visual storyteller arjunraj illustrates:

“It’s not like you click a button and it’s all done…having worked with it for one year almost. I’ve seen there is a specific way to engineers these prompts that will give me good results.”

Jeffrey Choy and Hidden Keileon take an informed approach – they understand the types of codes and data used in generative AI. Consequently, the collective develops their own datasets of images using LoRA software for interactive exhibitions including one that explored the traumatic global legacy of tear gas exposure.

Navigating intellectual property

AI technologies challenge core concepts in intellectual property regarding „authorship“, as well as „work“, given generative AI systems are trained on datasets comprising human created works (Smits & Borghuis 2022). Creative users struggle deciphering which images are authorized or not. Consequently, interviewees develop complex workarounds to avoid potential copyright violations given the vagueness of global IP laws on AI.

British Chinese artist Donald Shek takes „a very light touch“ preferring to feed his own images into generative AI programs. Others undertake the time-consuming process of creating their own data sets, which can involve „using web scraping software to find images from public domains“, or use noncopyrighted artwork when replicating visuals based on a specific style (Daniah Alsaleh 2024, Jeffrey Choy 2024). Some of the interviewees find safety using AI generated images in the early stages of the creative process from creating mood boards to conceptualizing fictional characters for a book.

Impacts on cultural entrepreneurialism

Emotional labor and entrepreneurialism are integral to how creatives mitigate precarity in their lives (Ashton 2021). They expend significant amounts time and energy on securing grants and income (Ashton 2021). AI tools potentially assist cultural entrepreneurs in developing those new work competencies that are integral to generating new opportunities.

Uros Rankovic runs a Belgrade based theatre company. Chat GPT and Midjourney help him source grant applications from afar as well as analyze complex funding callouts. He says, “I ask Chat GPT: Could you find me any grants related to these topics and he generates some links or websites…of course you need to check if these things exist“. However, “the quantity of applications may have increased“, but it does not guarantee funding (arjunraj 2024). Others draw on their own funds generated from projects or residencies to pay for monthly subscriptions of AI tools. It appears that maintaining usage and mastering these tools adds another layer to the arduous noncreative work that burdens cultural entrepreneurs.

Obsolescence of human creativity?

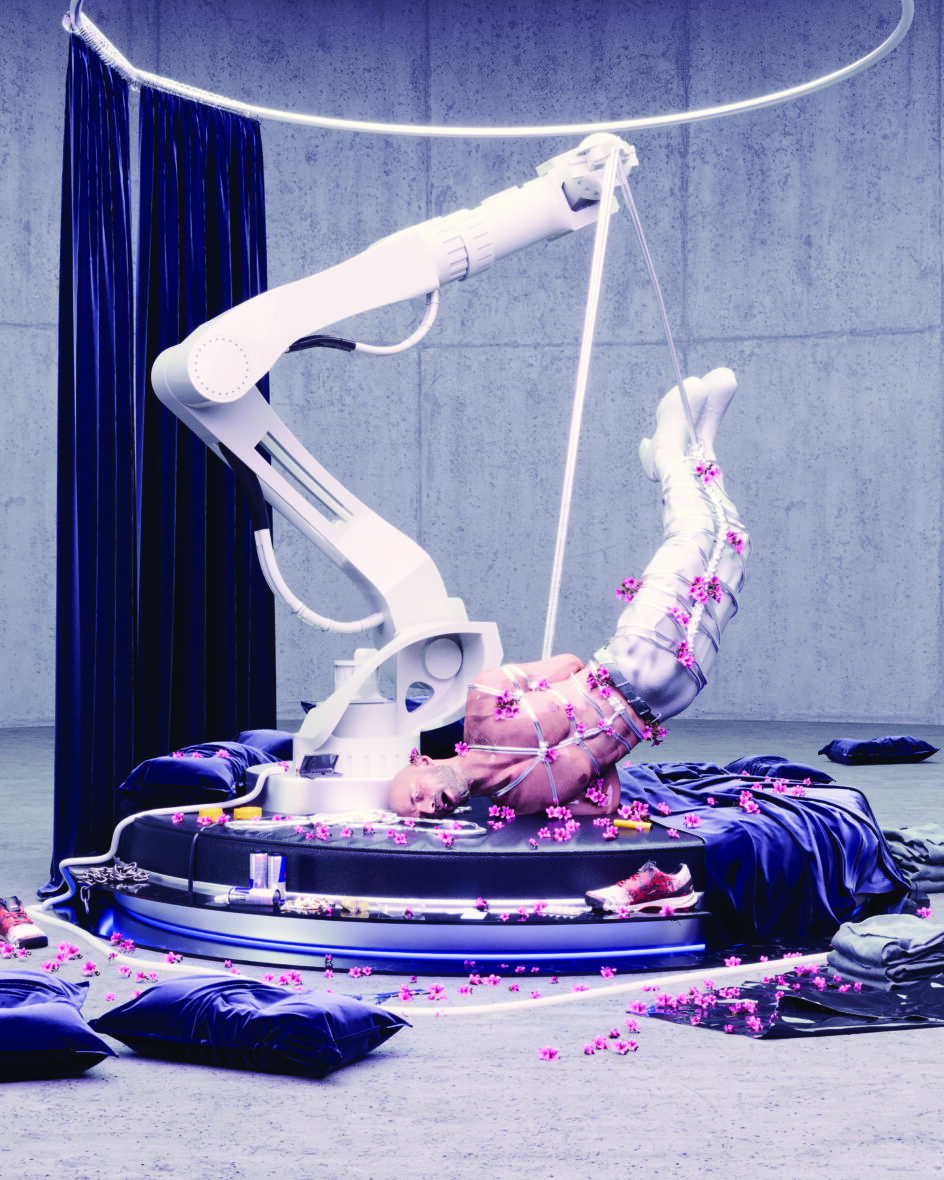

There is the concern of how AI technology “robotizes mental labor”, potentially negating the role of human creativity (Jin 2020: 23). Interviewees such as 3D conceptual artist Giorgios Ouzounis (Super_G_) believe AI technologies cannot replace the uniqueness of the creative spirit. He/she says, “you still need human consciousness. You still need you because it’s your art”. Participants highlight human collaborations, and unique storytelling are more conducive to sustainability than AI technologies.

What next?

Overall, cultural entrepreneurs find themselves in a double bind as they see the necessity of adopting AI tools for creative impact. Yet, there is the monotony of non-creative work that goes into the effective running of AI technologies (Ashton 2022). It remains to be seen if AI technology can alleviate their lived experiences of precarity and inequality.

Interviewees say underrepresented cultural entrepreneurs need to be highly visible in policy conversations about the development and regulation of AI technologies so they can effectively challenge harmful representations and narratives.

Interventions need to happen around governance, funding, training, and access as well as implementing protocols and standards around usage (Black et al 2024). However, it’s vital there is an awareness of the impact of AI technologies in tandem with precarity and inequality on the lived experiences of cultural entrepreneurs from underrepresented communities, especially when addressing what can contribute to a resilient and egalitarian creative economy.

Acknowledgements

With thanks to arjunraj, Daniah Alsaleh, Jeffrey Choy at Hidden Keileon, Sally Meeson, Giorgios

Ouzounis (Super_G_), Uros Rankovic, & Donald Shek

Images: (1) © Ouzounis Georgios Super G, (2) © Han Xiangzi

Bibliography

Ashton, D. (2021). Cultural organisations and the emotional labour of becoming entrepreneurial. Poetics, 86, 101534.

Ashton, D. (2022). Creative Work and Artificial Intelligence: Imaginaries, Assemblages and Portfolios. Transformations (14443775), (36).

Black, Suzanne R., Bilbao, Stefan, Moruzzi, Caterina, Osborne, Nicola, Terras, Melissa, and Zeller, Frauke. (2024). The Future of Creativity and AI: Views from the Scottish Creative Industries. A Report from Creative Informatics. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10805253

Brook, O., O’Brien, D., & Taylor, M. (2020). Is culture good for you?. In Culture is bad for you (pp. 26-53). Manchester University Press.

Comunian, R., & England, L. (2020). Creative and cultural work without filters: Covid-19 and exposed precarity in the creative economy. Cultural trends, 29(2), 112-128.

Kulesz, O., (2018). Culture, platforms & machines: the impact of artificial intelligence on the diversity of cultural expressions. Intergovernmental Committee for the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions. UNESCO

Hesmondhalgh, D., & Baker, S. (2011). Toward a political economy of labor in the media industries. The handbook of political economy of communications, 381-400.

Jin, D. Y. (2021). Artificial intelligence in cultural production: Critical perspectives on digital platforms. Routledge.

McRobbie, A. (2018). Be creative: Making a living in the new culture industries. John Wiley & Sons.

Amabile, T. M., & Pratt, M. G. (2016). The dynamic componential model of creativity and innovation in organizations: Making progress, making meaning. Research in organizational behavior, 36, 157-183.

Saha, A. (2018). Race and the cultural industries. John Wiley & Sons.

Siemon, D., Strohmann, T., & Michalke, S. (2022). Creative Potential through Artificial Intelligence: Recommendations for Improving Corporate and Entrepreneurial Innovation Activities. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 50, 241-260. https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.05009

Sobande, F., Hesmondhalgh, D., & Saha, A. (2023). Black, Brown, and Asian cultural workers, creativity and activism: The ambivalence of digital self-branding practices. The Sociological Review, 71(6), 1448-1466. https://doi.org/10.1177/00380261231163952B

Smits, J., Borghuis, T. (2022). Generative AI and Intellectual Property Rights. In: Custers, B., Fosch-Villaronga, E. (eds) Law and Artificial Intelligence. Information Technology and Law Series, vol 35. T.M.C. Asser Press, The Hague. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6265-523-2_17