Digital Crosscultural Multidisciplinary Collaborations in the Arts: Navigating Pros, Cons and Organisational Strategies

by Alexandra Tzanidou

Digital Cross-cultural Multidisciplinary (D2CM) collaborations in the arts are transforming artistic collaboration in the digital age. These projects unite creators from diverse culture backgrounds and disciplines using digital technology, enabling collaboration across geographical boundaries.

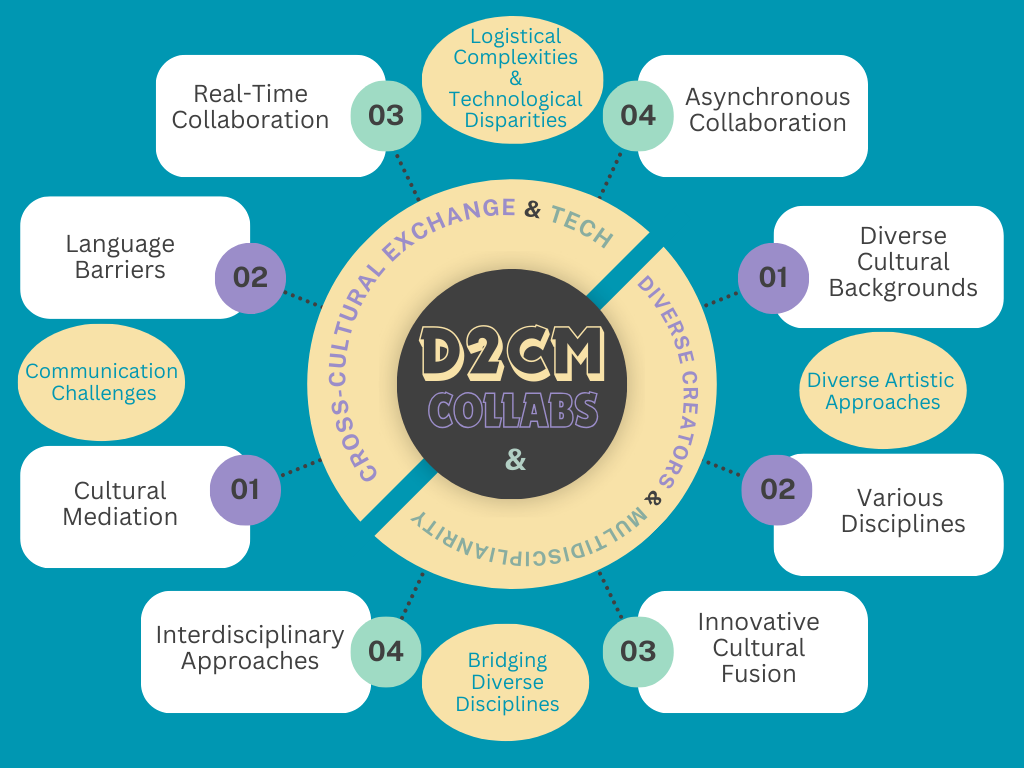

Defining D2CM Collaborations

Image 1. D2CM Collaborations consistence

D2CM collaborations are cultural projects that:

- Unite creators from different cultural backgrounds and disciplines

- Use digital means to bridge physical distances

- Enable real-time & asynchronous collaboration across continents and time zones

While offering significant potential, D2CM collaborations face unique challenges, including communication barriers, cultural misunderstandings, and logistical issues. Overcoming these obstacles is crucial for the success and impact of these projects.

This article explores the dynamics of D2CM collaborations, drawing insights from a real-world example: the “Çarşema Zîpa: Voices of Tradition and Inclusion” project realised under the umbrella of VAHA1. This initiative brings together three diverse partners: a Cultural Hub from Turkey consisting of 3 artistic groups2 that came together to focus on a project for preserving Kurdish culture through theatre, an inclusive theatre ensemble from Athens3 advocating for inclusion in the arts, and a grassroots innovation movement from Lesvos4 working on refugee integration through recycled art.

By examining the orchestration of this project, we delve into the intricacies of D2CM collaboration, with a particular focus on the communication challenges encountered and the strategies employed to overcome them.

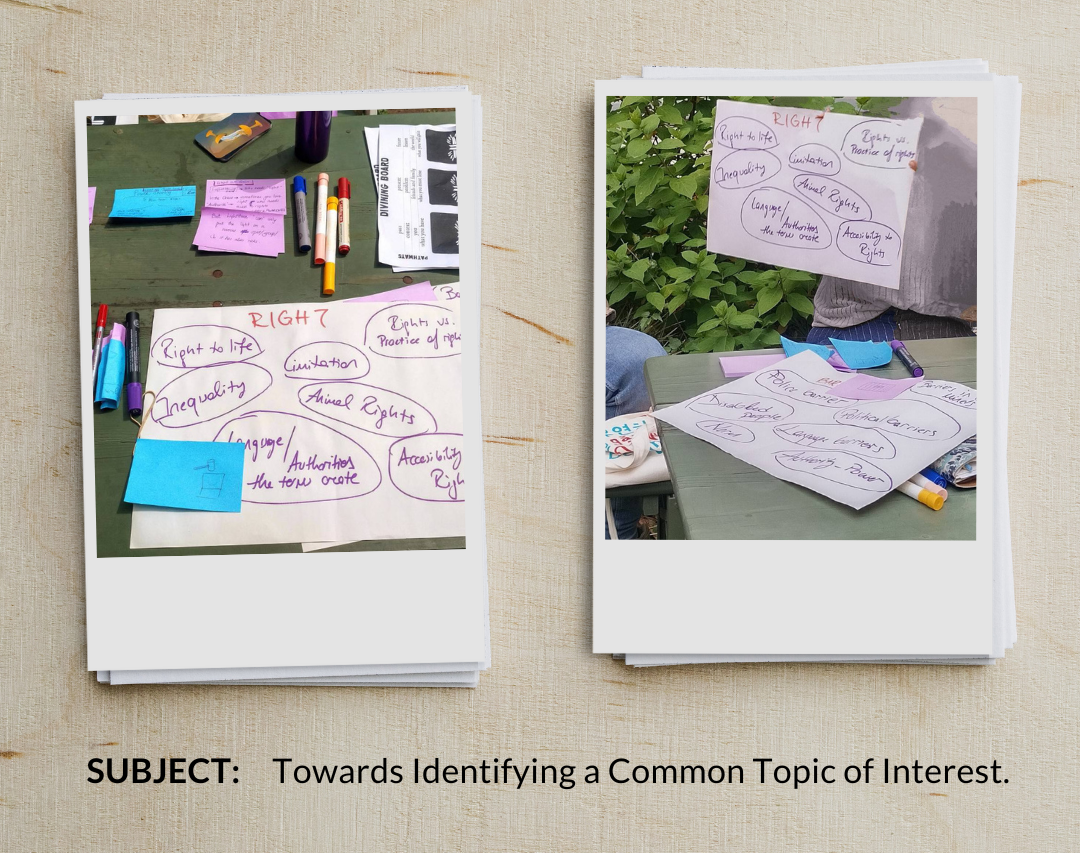

Image 2. Workshop for identifying common views and interests before going digital.

Image 3. Negotiating the present and the future on inclusion with the help of cards, before

going digital.

Communication Challenges

Based on the Oxford Dictionary, “Art is the expression or application of human creative skill and imagination [..] producing works to be appreciated primarily for their beauty or emotional power“5. According to Gaugin, “Art is either plagiarism or revolution”6 and to Warhol, “Art is what you can get away with”7.

Based on those definitions, who is the person who is tasked with translating not just words but emotional power, revolution, or the intangible essence of artistic expression in the absence of a common language?

In the absence of a mutual communication channel

We initially worked with a human translator to bridge the language gap in our collaboration. Moving forward, the Turkish hub chose a dedicated person to act as a project manager and translator. The focus on translating the language and identifying an issue of common interest, combined with the limited time for drafting a project proposal, resulted in documenting the main idea and leaving crucial aspects for the realisation of the project, such as the budgeting and the organisation, to a later stage. This situation guided us to a dead-end, lengthy Telegram-mediated dispute that concluded with compromises by all sides, which significantly reduced the initial creative energy, mainly due to the feeling that some sides lacked access to critical information.

Through this process, it became evident that the translator in a D2CM collaboration becomes more than a linguistic interpreter; they transform into a cultural mediator, an artistic liaison, and sometimes, a curator of ideas. Their role extends beyond word-for-word translation to encompass cultural mediation, emotional resonance, artistic terminology, conceptual misunderstanding, and non-verbal communication.

By this initial stage, the main learnings are:

- A need to include dedicated cultural mediators who will not directly associate with any creative groups and will accompany the whole project.

- Essential aspects of the project, such as the vision, an outline, the budgeting, and the process, need to be written and agreed upon before initiating the project.

- A need for transparency in the entire process regarding the existing, available, and future funding and resources for a specific project by all the stakeholders.

In the absence of a project partner

In any type of collaboration, it is unfortunate but expected, and in my stance accepted, that absence for several reasons can happen. But how should the absence of a core member of the organisational chain of the project be handled primarily in remote collaborations that fall under the umbrella of creative industries, where, in most cases, the qualitative input of a partner cannot be substituted or neglected?

In our case, this issue came early in the design process. Therefore, we established an ad-hoc mechanism to mediate this sensitive issue by asking the absent project partner to provide the green light to one of the other partners to speak in their regard. In written messages, the dedicated project partner informed the absent partner of all the developments, and the silent contract stated that the absence of a reply meant an agreement.

One of the main characteristics of this phase was the need for flexibility. However, from an organisational perspective, a provision of such situations would be beneficial. Therefore, the contracts must include: 1. At least one more person of reference informed about the project by each organisation and 2. A provision about a potential need for an unexpected handover to another stakeholder, such as who this stakeholder should be and the preferred method of communication, if communication is possible.

Mediating a Productive Mess

Despite the interest that accompanied discussions that enabled learning of diverse cultures and habits, navigating multi-language organisational meetings was always frustrating for all sides. As for participants who speak all the languages, this means listening repeatedly to the same information and for the rest to be excluded repeatedly from the discussion. Moreover, a simultaneous translation significantly increases the time of discussion.

Digital communication might not have achieved the best performance in real-time translated captions, but they can assist this type of communication. However, speaking either for asynchronous or synchronous communication, all participants must be aware that automated translation can potentially create misunderstandings. Our multicultural team mediated this productive mess by accompanying our statements with the intended feeling in cases where the discussion was becoming more intense.

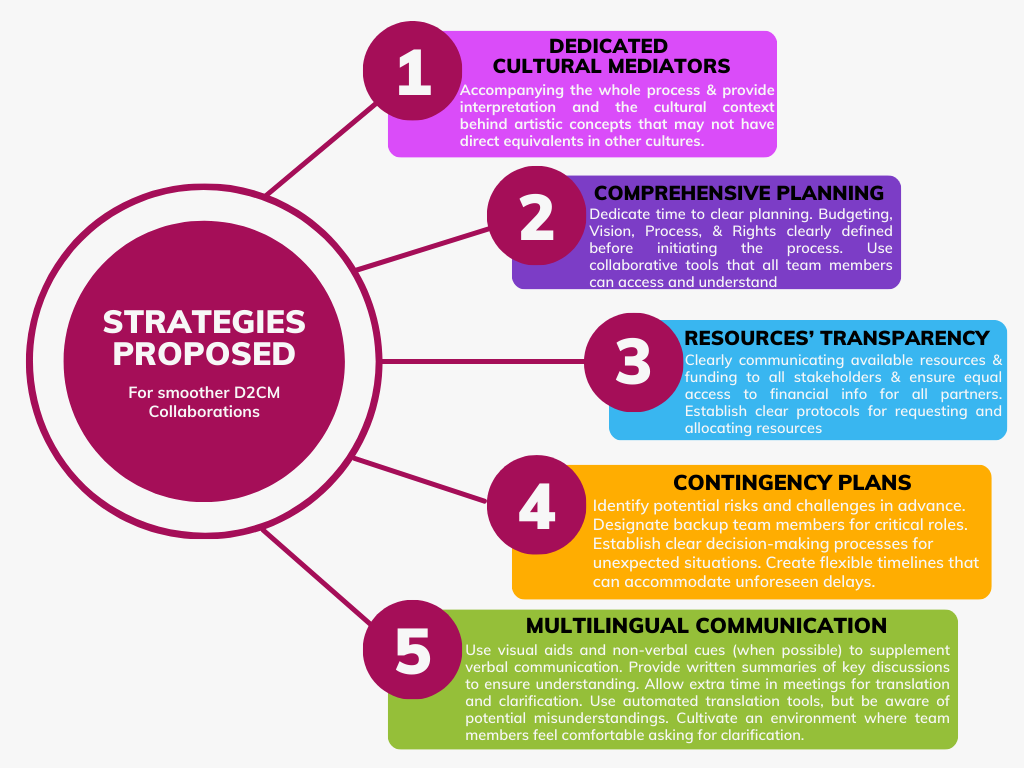

Focusing on the challenges of D2CM collaborations and the challenges connected to communication, the key insights derived from this study highlight several crucial aspects of

them, such as:

- The Role of Cultural Mediators

- Comprehensive Project Planning

- Transparency in Resources and Funding

- Development of Contingency Planning

- Effective Multilingual Communication Strategies

Image 4. Proposed Strategies for Smoother D2CM Collaborations

As D2CM collaborations continue to evolve, it is clear that they offer immense potential for artistic innovation and cultural exchange. By implementing the strategies and insights discussed in this article, artists and organisations can create more robust, inclusive, and impactful D2CM collaborations and overcome the unique challenges inherent in these complex partnerships.

- VAHA. https://vahahubs.org/ ↩︎

- VAHA. https://vahahubs.org/hubs/labhub ↩︎

- ΘΕΑΜΑ | Θέατρο Ατόμων Με Αναπηρία. https://theamatheater.gr/en/home-eng/ ↩︎

- LESVOSSOLIDARITY. https://lesvossolidarityshop.org/pages/about-us ↩︎

- “art”. The Oxford Pocket Dictionary of Current English. Retrieved August 15, 2024 from Encyclopedia.com ↩︎

- Garrison, A. (2021, February 24). Paul Gauguin Defined by His Paintings. Canvas: A Blog by Saatchi Art. ↩︎

- Licensing – The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. (n.d.).

↩︎